Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Hey Curt, whaddya

think of Vancouver?

Local legend Curt Lang made the city his base for a creatively

unconventional life. But what did he think of the place?

Greg Klein | September 3, 2016

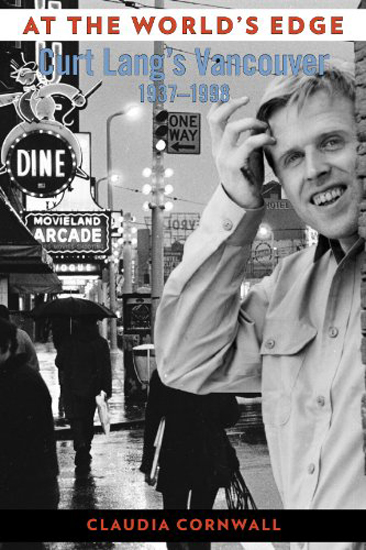

At the World’s Edge: Curt Lang’s Vancouver 1937-1998

by Claudia Cornwall 2011

Faint praise can be so damning. But that wasn’t Claudia Cornwall’s intention when she described Curt Lang as one of the “two hippest guys in Vancouver during the late fifties and sixties.” And maybe in the context of those times, before “hip” became a euphemism for poseur, that really was the compliment Cornwall intended. Even so, the appellation would hardly do justice to the “beatnik, poet, painter, photographer, beachcomber, boat builder, fisherman and software entrepreneur.” Cornwall performs an admirable feat of researching and portraying this guy’s exceptional life.

Born in 1937, Lang spent much of his childhood and adolescence living in Renfrew Heights, a neighbourhood of saltbox houses built for WWII veterans in what was possibly already a contender for the world’s most boring East End. Lang attended Gladstone, although Tech was much closer, doing badly in school despite his obvious intelligence. He dropped out months before graduation, maybe as a matter of principle.

Amazingly, one former teacher brought Lang and his friend Al Purdy to Malcolm Lowry’s North Van squatter’s shack. Lowry later described them as “wild western poets,” heaping special praise on the youngest. “This fellow Curt Lang was scarcely out of his teens and he impressed me mightily as being a type I thought extinct, namely all poet, whose function is to write poetry.”

That was a recommendation to an anthology editor, who wasn’t able to contact the transient. For a while Lang moved around Canada and tramped through Europe. There he was alternately broke, getting by on short-term jobs or sponging off women. Back in Vancouver—he pretty much re-settled there except when working up and down the coast—he took on the roles that Cornwall enumerated. As his younger brother Greg tells the author, he was either a quick study or a bluffer, depending on whom you listened to.

Could he have been both? Detractors might find his painting an easy target. Lang took it up in early adulthood, then quickly presumed to tell other artists how it should be done. His efforts at museum exhibit design and building demolition were decidedly dilettantish. And surely he was joking about inventing helium suits so people could leap long distances.

But he endured real poverty to continue writing, sold working boats that he taught himself to design and build, and succeeded at rugged, dangerous coastal enterprises. By the late ’80s, he dreamed up a digital device that could measure three-dimensional shapes. A lengthy, enormous collaboration with software engineers and (much less to Lang’s liking) business execs brought about a successful company, a multi-million-dollar takeover and hundreds of jobs.

Then there were his social relationships: the friendships, collaborations, pranks, arguments, fights, marriages and affairs. Lang enjoyed popularity with women but took them for granted, to say the least.

Those are a few details of a highly adventurous, self-reliant and probably genuinely brilliant individual who lived on his own terms. Just weeks before dying of cancer in 1998, he stated: “I write occasional poetry—not as a career—but as an activity that makes me feel that I am a free man and can exercise my free will.”

Free will, independence, creative and constructive unconventionality—that was Lang as portrayed by Cornwall.

But her subtitle, Curt Lang’s Vancouver, might disappoint those wanting to learn more about the city of that period. Readers do get that in the early parts of the book, with references to the Hotel Vancouver squat, East Van, beat and jazz hangouts, beer parlours, the cheap rooms amenable to bohemia, the terminal city from where Lang got work on coastal boats, went beachcombing and fished commercially. But as Cornwall’s story of Lang progresses, we experience less of the city.

As one of Vancouver’s “hippest guys,” for example, what did he think of the hippie movement, manifested so strongly in Vancouver but ignored in this book? Did he have thoughts on the transition of “hip” to fashion and then convention, and of political activism to political correctness? All the while Vancouver became inundated with addicts and lunatics, encouraged by a growing industry of poverty pimps. At the same time a rich, foreign elite moved in. All that was well underway by Lang’s death.

Of course he might not have seen it that way at all. But how did he see it? We’re not told. Maybe he lived in blissful oblivion, immersed in his own creativity.

Maybe, but Cornwall’s book reproduces dozens of photos Lang shot in 1972. Most of them capture a Vancouver that was already passing away—people and places doomed for near extinction (although a few can still be found). Is something missing from Cornwall’s account?

She knew Lang for his last decade or so and says their many topics of conversation included “current politics (where Curt and I were often miles apart).” Did that put Lang’s ideas beyond the pale? Cornwall later wrote for the Tyee, a website bankrolled by special interests that consider very little to be within the pale.

She does seem to relate his legacy, among it the poetry, the photography, the software company and his influence on others (by no means always positive). Her portrayal also suggests he was a product of Vancouver, at least in the sense that his talents would have played out differently had he grown up elsewhere. But what he thought of the place, we’re not told.