Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

DRC on the brink

The Congo’s increasing instability

heightens critical minerals concern

Greg Klein | January 3, 2019

Update: In what’s been called the DRC’s first peaceful transfer of power since 1960, Felix Tshisekedi was sworn in as president on January 24. That follows a controversial election in which two parts of the country had voting delayed until March and supporters of candidate Martin Fayulu accused the electoral commission of rigging the results in favour of Tshisekedi, who they say struck a pact with outgoing president Joseph Kabila. Catholic church observers had earlier disputed the outcome and Fayulu asked the Constitutional Court to order a recount. “The court, made up of nine judges, is considered by the opposition to be friendly to Kabila, and Fayulu has said he is not confident that it will rule in his favour,” Al Jazeera reported.

This is the place that inspired the term “crimes against humanity.” As a timely new book points out, American writer George Washington Williams coined that phrase in 1890 after witnessing the cruel rapaciousness of Belgian King Leopold II’s rubber plantations in the country now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. After rubber, the land and its people suffered exploitation for ivory, copper, uranium, diamonds, oil, ivory, timber, gold and—of increasing concern for Westerners remote from the humanitarian plight—cobalt, tin, tungsten and tantalum. Controversy over recent elections now threatens the DRC with even greater unrest, possibly full-scale war.

The country of 85 million people typically changes governments through coup, rebellion or sham elections. Outgoing president Joseph Kabila ruled unconstitutionally since December 2016, when his mandate ended. He belatedly scheduled an election for 2017, then postponed it to last December 23 before pushing that date back a week. The December 30 vote took place under chaotic conditions and with about 1.25 million voters excluded until March, a decision rationalized by the Ebola epidemic in the northeast and violence in a western city.

The epidemic marks the second-worst Ebola outbreak in history, the DRC’s tenth since 1976 and the country’s second this year. Although the government delayed regional voting on short notice, the health ministry officially recognized the current epidemic on August 1.

Responsible for hundreds of deaths so far, this outbreak takes place amid violence targeting aid workers as well as the local population. Like other parts of the country, the region has dozens of military groups fighting government forces for control, and each other over ethnic rivalries and natural resources. The resources are often mined with forced labour to fund more bloodshed.

With no say from two areas that reportedly support the opposition, a new president could take office by January 18. Already, incumbent and opposition parties have both claimed victory.

Voting in two regions has been delayed

until after the new president takes office.

(Map: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency)

Kabila chose Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary as his successor candidate but didn’t rule out a future bid to regain the president’s office himself.

Election controversy contributed to additional violent protests in a month that had already experienced over a hundred deaths through ethnic warfare as well as battles between police and protesters. Yet that casualty toll isn’t high by DRC standards.

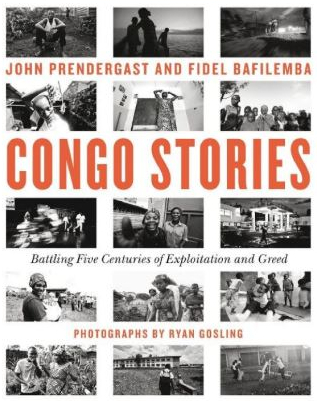

Published just weeks before the election, Congo Stories by John Prendergast and Fidel Bafilemba relates a harrowing story of a country the size of Western Europe that’s fabulously rich in minerals but desperately poor thanks to home-grown kleptocracies and foreign opportunists. Forced labour, war and atrocities provide a deeply disturbing backdrop to the story of conflict minerals.

According to 2017 numbers from the U.S. Geological Survey, the DRC supplied about 58% of global cobalt, 34.5% of tin and 28.5% of tantalum. The U.S. has labelled all three as critical metals essential to uses including defence, communications, medical care and consumer electronics. Tin and tantalum, along with tungsten and gold, are currently the DRC’s chief conflict metals, Prendergast and Bafilemba note. In addition to Congo tantalum, the world got 30% of its supply from DRC neighbour Rwanda, another source of conflict minerals.

Prendergast and Bafilemba outline the horror of the 1990s Rwandan Tutsi-Hutu bloodshed pouring into the Congo, making the country the flashpoint of two African wars that involved up to 10 nations and 30 local militias. During that time armies turned “mass rape, child soldier recruitment, and village burnings into routine practice.”

For soldiers controlling vast swatches of mineral-rich turf, rising prices for gold and the 3Ts (tantalum, tungsten and tin) provided an opportunity “too lucrative to ignore.” Brutal mining and export operations drew in “war criminals, militias, smugglers, merchants, military officers, and government officials,” Prendergast and Bafilemba write. “Beyond the war zones, the networks involved mining corporations, front companies, traffickers, banks, arms dealers, and others in the international system that benefit from theft and money laundering.”

DRC leaders did well too. “Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled Congo from 1965 to 1997, is seen as the ‘inventor of the modern kleptocracy, or government by theft,’” Prendergast and Bafilemba state. “At the time of our writing in mid-2018, President Joseph Kabila is perfecting the kleptocratic arts.”

Westerners might be even more disturbed to learn of other beneficiaries: Consumers “who are usually completely unaware that our purchases of cell phones, computers, jewelry, video games, cameras, cars, and so many other products are helping fuel violence halfway around the world, not comprehending or appreciating the fact that our standard of living and modern conveniences are in some ways made possible and less expensive by the suffering of others.”

Not all DRC mines, even the artisanal operations, are considered conflict sources. But increasing instability could threaten legitimate supply, even the operations of major companies.

The example of Toronto-listed Glencore subsidiary Katanga Mining, furthermore, shows at least one big player failing to rise above the country’s endemic problems. In mid-December Katanga and its officers agreed to pay the Ontario Securities Commission a settlement, penalties and costs totalling $36.25 million for a number of infractions between 2012 and 2017.

Katanga admitted to overstating copper production and inventories, and also failing to disclose the material risk of DRC corruption. That included “the nature and extent of Katanga’s reliance on individuals and entities associated with Dan Gertler, Gertler’s close relationship with Joseph Kabila, the president of the DRC, and allegations of Gertler’s possible involvement in corrupt activities in the DRC.”

In December 2017 the U.S. government imposed sanctions on Gertler, a member of a prominent Israeli diamond merchant family, describing him as a “billionaire who has amassed his fortune through hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of opaque and corrupt mining and oil deals” in the DRC.

“As a result, between 2010 and 2012 alone, the DRC reportedly lost over $1.36 billion in revenues from the underpricing of mining assets that were sold to offshore companies linked to Gertler.”

Just one day before imposing sanctions, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order calling for a “federal strategy to ensure secure and reliable supplies of critical minerals.” Approaches to be considered include amassing more geoscientific data, developing alternatives to critical minerals, recycling and reprocessing, as well as “options for accessing and developing critical minerals through investment and trade with our allies and partners.”

Unofficial DRC election results could arrive by January 6. Official standings are due January 15, with the new president scheduled to take office three days later. Should the Congo see a peaceful change of government, that would be the DRC’s first such event since the country gained independence in 1960.

January 7 update: The DRC’s electoral commission asked for patience as interim voting results, expected on January 6, were delayed. Internet and text-messaging services as well as two TV outlets remain out of service, having been shut down since the December 30 election ostensibly to prevent the spread of false results. On January 4 the U.S. sent 80 troops into nearby Gabon in readiness to move into the DRC should post-election violence threaten American diplomatic personnel and property. The United Nations reported that violence in the western DRC city of Yumbi over the last month has driven about 16,000 refugees across the border into the Republic of Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville.