Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Potosí’s legacy

A renowned but notorious mountain

of silver looms over Bolivia’s turmoil

Greg Klein | December 5, 2019

In the heart of the Andes, 4,000 metres above sea level,

the city of Potosí sits beneath the infamous Cerro Rico.

(Photo: Shutterstock.com)

Far overshadowed by the political violence plaguing Bolivia over the last several weeks was a slightly earlier series of protests in the country’s Potosí department. Arguing that a proposed lithium project offered insufficient local benefits, residents convinced then-president Evo Morales to cancel a partnership between the state-owned mining firm and a German company that intended to open up the country’s vast but unmined lithium resources.

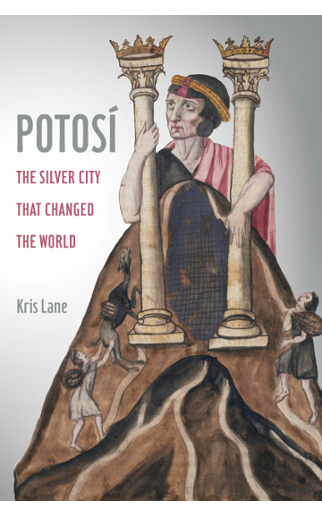

Other events overtook the dispute, sending Morales into exile and the country towards an uncertain future that could bring elections, military coup or civil war. Yet Potosí serves as a stark example of Bolivia’s plight: a mineral-rich land that’s one of South America’s poorest countries. That’s one of the contradictions related in Kris Lane’s recent book Potosí: The Silver City that Changed the World.

Unlike so many other New World mineral rushes, the 16th-century discovery held enduring global importance. More typically, and probably more dramatically, it was “rife with paradox from the start, a site of human depravity and ingenuity, oppression and opportunity, piety and profligacy, race mixture and ethnic retrenchment,” Lane recounts. “The list could go on.”

Looming over a boom town both squalid and magnificent was the great mountain of silver, Cerro Rico—“easily the world’s richest silver deposit.” For their first century of operation its mines and mills churned out nearly half the world’s silver, and then about 20% up to 1825. “The red mountain of Potosí is still producing silver, tin, zinc, lead, and other metals, and it never seems to have stopped doing so despite many cycles since its discovery in 1545.”

This huge supply came online just as Europe was suffering a “bullion famine,” Lane writes. More than gold, silver served as the world’s exchange medium. Globalization can be dated to 1571, when Spain launched trans-Pacific trade and Chinese demand for silver “reset the clock of the world’s commercial economy just as Potosí was hitting its stride.”

Yet Spain served as little more than a transfer point for its share. With longstanding armed conflicts on a number of fronts, “the king’s fifth went to fund wars, which is to say it went to pay interest on debts to Charles V’s and Philip II’s foreign creditors in southern Germany, northern Italy, and Flanders.”

As for the rest, “once taxed, most private silver went to rich merchants who had advanced funds to Potosí’s mine owners. They then settled their accounts with distant factors, moving massive mule-loads and shiploads of silver across mountains, plains, and oceans. Global commerce was the wholesale merchants’ forte, and most such merchants were junior factors linked to larger wholesalers in Lima, Seville, Lisbon, and elsewhere. Some had ties to Mexico City and later to Manila, Macao, and Goa; still others were tied to major European trading hubs such as Antwerp, Genoa, and Lyons.”

But wealth wasn’t unknown near the source. Known for its “opulence and decadence, its piety and violence,” the boom town “was one of the most populous urban conglomerations on the planet, possibly the first great factory town of the modern world…. By the time its population topped 120,000 in the early seventeenth century, the Imperial Villa of Potosí had become a global phenomenon.”

It was also a “violent, vice-ridden, and otherwise criminally prolific” contender for the world’s most notorious Sin City.

By comparison the much-later Anglo-Saxon boom towns seem small time, only partly for their ephemeral nature. But the men (and later women) who moiled for Potosí silver weren’t the adventurous free spirits of gold rush legend. Slaves and, to a greater extent, conscripted Andean natives endured the inhumane conditions “perhaps exceeded only by work in the mercury mines of Huancavelica, located at a similarly punishing altitude in Peru.”

At the same time some natives, like some foreigners, achieved affluence as merchants, contractors or traders in bootleg ore boosted by the conscripts. Andean innovation helped keep the mines going, for example by smelting with indigenous wind furnaces after European technology failed, and using a native method of cupellation.

“Put another way, native Andeans and Europeans began a long process of negotiation and struggle that would last beyond the end of the colonial era. Potosí’s mineral treasure served as a fulcrum.”

A “noisy, crushing, twenty-four-hour polluting killer, a monster that ate men and poisoned women and children” needed some rationale for its existence. Spain’s excuse was the money-burning responsibility of defending the faith.

“The steady beat of Potosí’s mills and the clink of its newly minted coins hammered away at the Spanish conscience. Priests, headmen, and villagers, even some local elites denounced the mita [forced native labour] as immoral. As one priest put it, even if the king’s demand for treasure was righteous, [the] Potosí and Huancavelica mitas were effectively killing New World converts in the name of financing the struggle against Old World heresy. God’s imagination could not possibly be so limited.”

More practical matters stained the empire’s reputation too, as the 1649 Potosí mint debasement scandal unfolded. World markets recoiled and Spain’s war efforts suffered as money lenders and suppliers refused the once-prized Spanish coins. “Indeed, the great mint fraud showed that when Potosí sneezed, the world caught a cold.”

With the 1825 arrival of Simón Bolívar, “the Liberator symbolically proclaimed South American freedom from atop the Cerro Rico. Yet British investors were close on his heels.”

Foreign owners brought new investment and infrastructure. But “the turn from silver to tin starting in the 1890s revolutionized Bolivian mining and also made revolutionaries of many miners. The fiercely militant political sensibility of the Potosí miner so evident today was largely forged in the struggles of the first half of the twentieth century.”

Those clashes bring to mind events of recent weeks, in which dozens have been killed by police and military.

Lane’s narrative continues to Morales’ “seeming ambivalence” toward miners and Potosí’s transformation into a “thriving metropolis” that hopes tourism will offset mineral depletion. Meanwhile underpaid, often under-age, miners continue to toil in woefully unhealthy conditions.

The breadth of Lane’s work is tremendous. He covers Potosí’s history from global, colonial, economic and social perspectives, outlines different practices of mining and metallurgy, recites contemporary accounts and provides quick character studies of the people involved. All that gives his book wide-ranging appeal. Lane also offers considerable context for the present, as the geologically bountiful country once again experiences troubled times.