Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Europe R.I.P.

What does the old continent’s demise

mean to the New World?

Greg Klein | October 21, 2017

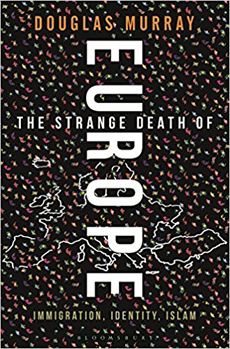

Inroads by Alternative für Deutschland notwithstanding, Douglas Murray wasn’t surprised by Angela Merkel’s historic election to a fourth term as chancellor of the country she’s done so much to destroy. The Spectator contributor has detailed the despairing condition of that continent in The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam. Pretty much anything that happens now—terrorism as “the new normal,” mass public sexual assaults, police and government cover-ups of mass public sexual assaults for fear of political correctness, honour killings, police and government cover-ups of honour killings for fear of political correctness, child pimping gangs, police and government cover-ups of… well, all of it’s already been documented to no avail. Europe is fading fast and the rest of the West can only follow.

If his book isn’t yet a post mortem, it’s a summary written at the bedside of a terminal case, one which acquiesced in its own destruction. That seems to puzzle Murray the most, because Europe’s death wasn’t so much inevitable as suicidal.

What started with extraordinarily lax immigration policies led to a Muslim onslaught that threatens to replace Western culture and values more efficiently than the earlier waves of workers, opportunists, bums and criminals. “All those who had warned about it had either been ignored, defamed, dismissed, prosecuted or killed,” Murray points out.

Over here, generations of Canadians have heard mass immigration described as necessary, originally for economic reasons, then to enrich our culture, then to create diversity (implying that’s not necessarily enrichment), and now for humanitarian reasons. Just as no mainstream voice ever challenged the earlier excuses, none asks how a supposed humanitarian crisis can mostly affect young men.

As for the Muslims pouring into Europe, they sure as hell don’t want to live in Muslim countries. Those Muslim countries, meanwhile, demonstrate indifference to refugees, genuine or otherwise. So in September 2016, when news broke that the body of a three-year-old Syrian boy had washed up on a Turkish beach, the Arab world remained unmoved. European countries, on the other hand, took the death “on their own consciences,” with newspapers calling it “Europe’s shame.” Never mind that the kid’s father had a secure job in Turkey but chose to gamble his family’s safety.

Not exactly exuding humanitarianism themselves, Arab migrants often detest sub-Saharan blacks, Murray writes, and on their Mediterranean voyages have been known to throw African Christians overboard. Other migrants capture and torture fellow migrants, sending their families horrifying cell phone videos to bolster the ransom demands. Much of the crime and rioting fake refugees commit once inside Europe goes unreported, even sexual assaults on a mass scale.

And this “humanitarian crisis” could very well be spurred on, in part, by Muslims who want to use Europe’s liberalism to conquer and overturn liberal Europe.

Murray discusses just about every aspect of the problem, including the Western birthrate. Citing evidence that many childless Europeans do want children, he suggests economic policies could address a largely economic problem.

More than any other cause, Murray attributes Europe’s self-destruction to the continent’s “unique, abiding and perhaps finally fatal sense of, and obsession with, guilt.” He devotes considerably less time to the self-righteousness of those who support the demographic revolution. But maybe that’s a difference between the Old World and Canada, where there’s very little guilt complex evident in the sanctimonious liberals who exalt in moral preening while vilifying their opponents.

Murray has endured his share of vilification for writing this book. But it’s surprising and maybe even a bit encouraging that someone from the mainstream would produce such a work. So what use is it—a very late, very last-minute warning? An indication of what threatens countries like Canada (although the book’s all but been ignored here)? A contribution to future historical study, if such a thing is permitted?

Or solace to the old and childless? While discussing economic causes of the European birthrate, he sees an additional possibility. If would-be parents “contemplate a future filled with ethnic or religious fragmentation, they may well think again about whether this is a world they want to bring their children into.”

Follow Douglas Murray here.