Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

They is there, too

Rediscovered stories depict the revenge

of the inadequate in 1970s England

Greg Klein | February 14, 2022

Strains of this tyranny can be apparent 40 hours a week: compulsory radio imposed non-stop all day long, more likely by co-workers than bosses; suspicion, even anger, towards anyone uninterested in TV, sports, cars, celebrities or consumer junk; seething resentment towards anything deemed non-average; implications that it’s unacceptable, almost criminal, not to be stupid.

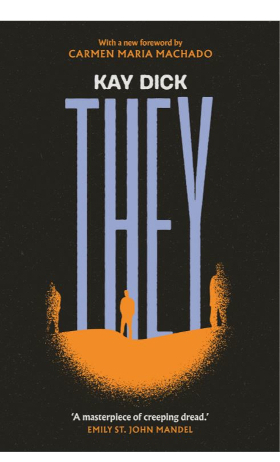

Imagine all that enforced ruthlessly by an all-powerful regime. Kay Dick’s recently rediscovered and republished 1977 work They: A Sequence of Unease presents just that scenario.

In a reflection of current tensions, They has been (sounds like woke grammar) heralded as a dystopian novel. Certainly the title brings to mind Yevgeny Zamyatin’s Soviet-inspired nightmare We, which in contrast is narrated by a regime conformist. But They is actually a collection of short stories, all variations on the same theme. With no progression from one story to another, any of the pieces could stand alone as an independent work. Each features the same protagonist and similar characters, along with a similar setting and mood. Dick expresses the mood largely through descriptions of weather and landscape, sometimes disrupted by sudden noises or sights that build a sense of encroaching menace.

The protag and her colleagues comprise a kind of post-industrial Arts and Crafts movement that’s taken refuge in rundown country homes near the southern English coast, something like the isolated monasteries that strove to preserve culture from barbarians intent on destroying what they couldn’t understand. A new government systematically outlaws individuality, with enforcement by both officials and citizens that’s so far sporadic but sometimes breathtaking for its malice, not to mention brutality.

Creative expression might be prevented by rendering artists blind or deaf, amputating tongue or hands, or maybe forcing an arm into fire for several minutes.

When cornered, some escape through suicide, surrender or treachery. Some work openly in defiance. Others wait hopefully for a reprieve, striking debate about passive resistance versus acquiescence. Some work discretely, trying to conduct themselves publicly like dull-average everybodies.

Not just creativity, but communication has been proscribed. So has the state of being single, but not to support family values. As one character explains, “They fear solitary living, therefore they envy it.”

“But they hardly speak to each other.”

“They have reduced speech to a minimum, to such an extent that they can barely articulate their words.”

TV is strongly encouraged, sometimes compulsory. In windowless asylums “the only light comes from television screens, kept on all the time. I’m told they don’t notice the noise or images after a while. At first it breaks them down. There’s a television set in every room.”

Release comes when inmates lose the ability to feel emotions and, most importantly, become cured of identity.

Single conformists band together to lose what identity they had. Families consist of unhappy little units of violent husbands, callous wives and cruel children. “Love is unsocial, inadmissible, contagious.” Tourist mobs travel the countryside to harass the creative holdouts who’ve thus far been left alone by official brutality.

Remaining artists struggle not only for survival but with the purpose of their vocation. “Can we go on creating for ourselves? Without any contact with the outside world?” The urge to create and preserve culture continues to inspire. One painter, though, is driven to suicidal defiance by the seductive inspiration of an 18th century garden.

These stories present amplified metaphors for artistic function, the need to create, the challenges that impede expression, and also the pressures to “fit in,” whether or not one’s an artist.

It’s worth noting, however, that 1970s England was far less philistine than Canada. Since then the Gleichschaltung has savaged both countries with approximately equal severity. But in previous decades English of all social classes were much more literate, articulate, observant and even contemplative than their Canadian counterparts. Even fucking stupid Limeys were less fucking stupid than stupid fucking Canuckleheads.

Possibly reflecting a warped sense of New World egalitarianism but more likely simple insecurity, you’re-not-average animosity prevailed much more strongly here than there. It probably still does.

That’s apparent in not only run-of-the-mill dull-ordinary Canadians but also the vengeful inadequates who teem so plentifully in Vancouver that they help define the city. That confused resentment also helps characterize the protest culture of Vancouver and the wider social revolution that sustains our regime.

Much of the publicity accompanying They’s re-release plays up the author’s lesbianism. Even without any indication of the protagonist’s leaning (although a forward added to the book insists the character is “ungendered”), the book has been heralded as a dystopian warning about intolerance towards homosexuals. Really straining that argument, the publisher calls They “a radical celebration of queerness … and a warning.”

Yet the homo/transsexual movement plays a major role in the demolition of the West, its arts and pretty much everything else but its decadence. That, despite the fact (well, actually partly because) no other society has such a prominent homosexual culture.

As for the West’s current “artists,” few of them have anything in common with Dick’s characters. Strongly supporting the all-destroying zeitgeist, the cultural elite adds a smug sense of superiority to the mix of resentment, ideology and opportunism that’s bringing outright tyranny, maybe preceded by chaos.

The author died in 2001 at age 84. What she thought of Western decline after 1977 hasn’t come to light in the book’s publicity. But if Dick intended this work as a dystopia, it’s one that’s already taken hold and with support that might have surprised her.