Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

When a wordsmith encountered

the Woodsmen of the West

This compelling account fell into obscurity,

probably because it took place in Canada

Greg Klein | August 29, 2016

Woodsmen of the West

M. (Martin) Allerdale Grainger

1908. Reprinted 1996 and 2010

What a marvel to be reminded of how recently the Canadian West emerged from the frontier—and how distant that frontier remains. Martin Allerdale Grainger wrote this book sometime between 1901 and 1908 during a boom in West Coast logging. An educated Englishman who had knocked around the Klondike, the Boer War and British Columbia logging camps, he brings an outsider’s perspective to a not overly reflective or literate world. The result might be a classic among first-hand chronicles of pioneer life and really should be better known.

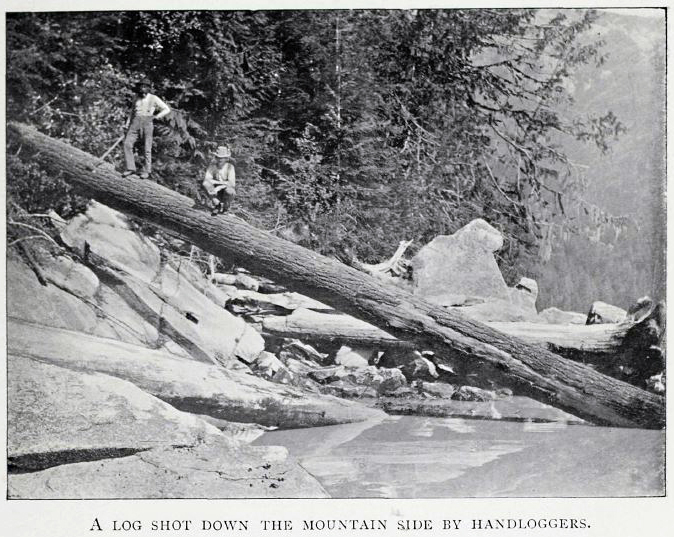

This was largely the world of small logging camps and of handloggers running their own outfits single-handedly or with one or two buddies, something like prospectors and placer miners.

Many of the place names have changed or disappeared, but much of the action takes place at the head of Knight Inlet (which Grainger calls Coola Inlet), and at wild west hotels on Hanson Island and someplace called Port Browning. The wilderness looms gloomy and threatening, the weather’s treacherously hot or relentlessly wet and the work’s very heavy and very dangerous.

Nevertheless, this middle class gent falls in with the rugged Canadians, Americans (a very fluid border back then) and others who, through necessity, adventure, avoidance of modernity or all of the above, become frontier jacks-of-all-trades. The same individual can become a middling to highly accomplished axeman, steamboat pilot, carpenter, blacksmith, machinist, cook and (not or) whatever else circumstances require.

Grainger’s account mostly covers his stint on an outfit run by partners Carter and Allen, an operation that grew from handlogging to a small camp consisting of three or four shacks floating on log rafts that could be towed from one logged-out desecration to another. Grainger initially finds dignity in work as he endures heavy labour, overcomes setbacks, picks up skills and stands up to the elements. Apart from logging he navigates (sometimes successfully) a decrepitly dangerous steamboat through menacing waters, improvising vital repairs on the go. Towards the end of the book he rows a heavily laden boat the entire stretch of Knight Inlet, even keeping pace with another boat handled by two men as his own tub leaks steadily. Earlier on, he recounts:

“I liked the spirit of the thing; the quiet feeling that it is natural and right that a man should never admit that he cannot do a thing; the feeling that things must be done, done ‘right now,’ kept on at until they are done; that one has ‘got to get a move on’ and work quickly. Not if the weather suits, or if circumstances are favourable, or if one’s calculations were correct, or unless one should be too tired…. There was very little if or unless about Carter and Allen.”

A good part of Woodsmen constitutes a character study of Carter, an increasingly loathsome character. He takes an egotistical pride in his part ownership of the camp, a steam donkey and the steamboat. One scene portrays the Nova Scotian thoroughly besotted, both from booze and grandiosity:

“‘All MINE,’ he croaked—‘my donkey, my camps, my timber, my steamboat there! Fifteen square miles of timber leases belong to me! Money in the Bank, and money in every boom for sixty miles, and hand-loggers working for me, and ME the boss of that there bunkhouse-full of men! Tell them swine at Port Browning I done it all! I and the donk! I!!’”

Scenes of drunkenness abound, usually in high-spirited revelry, occasionally in violence. Robert Service would have loved it.

But God Almighty, the extremes that alcoholism reached in those relatively drugless days. Many of the men don’t trust themselves with liquor at the camp. Some don’t trust themselves with liquor at all and see that as an incentive to stay on at the camp. Their withdrawal symptoms aren’t run-of-the-mill hangovers, they’re “the holy terrors,” days-long ordeals that some try to treat with painkillers, ginger, scent or cayenne pepper. One man sticks to his own treatment:

“I go and lie on the beach and take a good drink of seawater, and make myself good and sick, and stand it. It’s healthier for a man that way, and he will be fit for work before fellows what uses dopes has got their nerves to stop shaking.”

Dates aren’t given but the logging boom ends suddenly. This could be the Panic of 1907. Circumstances seem to push Carter right over the brink, making Grainger finally understand why other loggers revile the scumbag. By that time Grainger’s relieved to escape the heart of Knight Inlet darkness.

Of course the work is a product of its time. A rare reference to natives as anything but “Siwashes” refers to “an Indian gentleman who called in his canoe to try to trade his wife for whisky.”

(To put that in perspective, news stories this summer have reported at least two American women accused of prostituting their daughters for drugs.)

Grainger describes “stretches of forest whose sea-fronts he [Carter] had shattered and left in tangled wreckage. As for him, he was going to butcher his woods as he pleased. It paid!”

Grainger’s concern isn’t the environment. It’s the economic damage to inland-extending timber leases by logging only the easiest shoreline pickings.

But that was then. Grainger really captures the spirit of the time and place in a work that would help Canadians better understand their past.

An afterword to the 1996 reprint, however, can make readers wonder whether some Canadians are capable of such understanding. The essay first tries to argue that Woodsmen isn’t autobiography or history but a novel. Then, with far more tortured reasoning, it attacks Grainger’s masculinity and by extension that of other frontiersmen. The exercise just demonstrates the chasm between working people and Canada’s official culture.

Had Woodsmen been set in the U.S., Hollywood might have turned it into another Sometimes a Great Notion. Just as well that didn’t happen.

A different approach might have played out Down Under. As a nationally conscious Australian cinema came of age in the 1970s, the country’s filmmakers were said to be poring over historical, autobiographical and fictional accounts of previous generations. A work like this would surely have come to greater prominence.

Instead, we get a reprint with a weird attack on the writer and his contemporaries from a pseud trying to vandalize what she can’t understand.

The vandalism failed, unless it contributed to the book’s obscurity.

Download a copy of the original, with much better photo reproduction than the reprint.

A steam donkey among the forestry relics along Powell River’s Willingdon Beach Trail.